The theatre director says “The Fugue of Tjebolang”, a dreamy tale about gender fluid people journeying into the world, is also full of sex and possesses the potential to heal.

“I’m very much done excavating my pain for audiences,” says actor and theatre-maker Rehane Abrahams. “I want to find a way of infusing more life and more joy into the theatrical experience.”

Despite a three-decade theatre career, Abrahams is perhaps best known for playing the villain, Wendy Newman, in the popular Showmax telenovela, Arendsvlei. Earlier this year she won a Fleur du Cap for her dual role as Mercutio and Lady Montague in last year’s Maynardville production of Romeo and Juliet.

Her extensive career as a creator of new work has tended to focus on theatre that is ritualistic and decolonial in nature; there is inevitably an element of transformation, a desire to shift and heal. She does not make work purely for the sake of entertainment, but is instead intensionally searching for new ways of telling stories, and of creating theatre that lands differently.

There are even more curious clues as to her interests in her Instagram bio, where she describes herself as a “Somatic Decoloniser, Eco-Erotic liberator, Performance- Maker”. While it’s no simple thing to pin her down, what’s clear from talking to her is that she puts her heart and soul on the line in order to make work that is potent, important and truly original.

And she wants to create work that nourishes the audience, that adds to their experience of life rather than subtracting from it.

This objective has led to her latest stage creation, The Fugue of Tjebolang, which is premiering at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda on 26 June. It will also travel to Stellenbosch for Woordfees later this year.

It’s a new play that’s been centuries in the making. Conceived as an immersive, multivalent experience, it’s the theatricalisation of “Cebolang Minggat” (the Exile of Cebolang), a tale excerpted from the Serat Centhini, the great Javanese literary epic written in the form of suluk, verses intended for chanting.

Abrahams calls the story a “queer Islamic epic that is erotic”; she has incorporated dance, music and visual projections to create something she hopes will jolt audiences – “bring them to their senses” – and help liberate and heal.

Completed in 1815 and written in Sanskrit, Arabic and an ancient Javanese language, Kawi, the Serat Centhini comprises 12 volumes, 4,200 pages, 722 verses, and over 200,000 stanzas. It forms part of the Javanese babads, an encyclopaedic literary genre dealing with historic events and covering everything from art, religion and mysticism to erotic knowledge.

And some of it is pretty wild, much of it unexpected.

While it describes virtues that originate in Islam, it portrays Javanese people as sexually open and recognises eroticism as part of life, rather than as taboo. Some contemporary scholars find its explicit references to and descriptions of sexual intercourse pornographic and some of the language vulgar.

Reportedly, the “pornographic” parts were written by Pakubuwono V, crown prince and then king of Surakarta, who is said to have conducted such extensive research that he died of acute syphilis after only three years on the throne.

The manuscript was kept locked away in the palace and in the state’s archive for almost two centuries for fear of stirring public controversy, but Serat Centhini is now in the public domain, and was popularised by the French poet-cum-journalist Elizabeth D. Inandiak, after she found Sunaryati Sutanto’s French translation of the work, published as a 466-page book in 2002.

Abrahams, who lived in Bali for six years, discovered the tale of Cebolang/Tjebolang by accident. “I walked into a theatre in Central Java and the room was dripping with sex – the audience was so turned on,” she says.

“I was like, ‘Oh my god, what is happening?’ On the stage was a small, grey-haired French woman, reading.” Performing alongside the narrator was Slamet Gundono, a very large, very famous and quite avant-garde dalang, or shadow puppeteer.

“I was like, how in the hell is everybody so sexed up? It was this story of Tjebolang – the words! The audience was so turned on by what they were hearing that they were almost melting from the heat of it.”

Her initial encounter with the story made a huge impression, but when Abrahams then read it, the tale simply seemed too vast, and also “way too ridiculous”, to take on as a performance. And so it sat around for many years.

“I always felt like I had to do it,” she says, “but I didn’t know when I’d be ready – or when the world would be ready for it.”

Abrahams recently completed her PhD, the focus of which was “eco-erotic decolonisation”, and in the wake of all that research she says felt ready to tackle Tjebolang.

Adapting the script from Inandiak’s translation, she says she pared down the original, edited out some of the “inordinate amount” of sex. “There is a lot of it,” she says. “I salute him for it, but the crown prince really did a lot of research.”

The Fugue of Tjebolang is set to be at once hallucinatory and erotically charged, albeit with a strong spiritual core. Abrahams says it’s been the kind of project that has enabled her to rediscover the “older magic” of her childhood, when her fascination with storytelling included writing and performing puppet shows and plays for her classmates.

“There’s always been like a kind of magical thread in my storytelling,” she says.

That magic pervades both the type of story Tjebolang tells and the manner of its telling.

“There is a plot,” Abrahams says. “It’s a really simple story about a young person who feels betrayed his family and so goes on a kind of fool’s journey, a quest for knowledge. Eventually, he returns to his family, and to their love. So it’s like the prodigal child on a fool’s quest.”

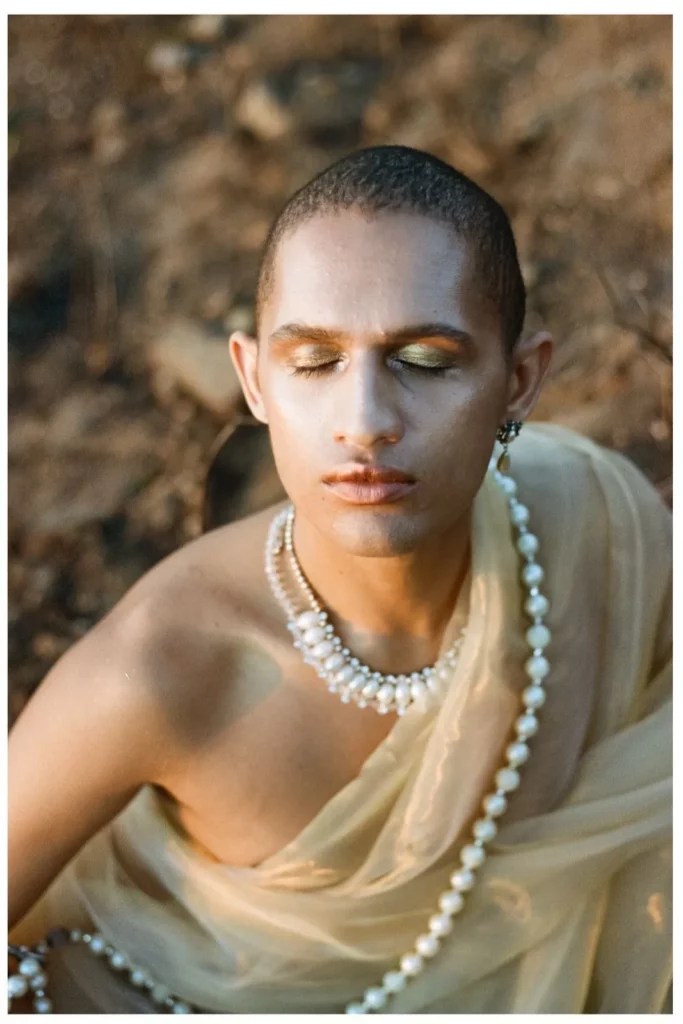

That journey has elsewhere been described as a “carnal adventure” during which the “seductive Tjebolang” (played by the artist/activist Cheshire V, aka C.C. Martinez) encounters an array of characters – among them prostitutes, hermits, Sufi scholars and medicine men.

Despite the narrative linearity, “the actors create worlds upon worlds upon worlds”, Abrahams says. “There are lapses of reason, too, so the characters in a sense penetrate a liminal space.”

The show includes choreography by Ina Wichterich, with classical Javanese dance elements. And it features not only large visual projections on three sides, but an immersive soundscape by Julia Theron and Denise Onen, whose “epic score” does “magical things”.

Keep reading on Cachet.

More information about FEC funded works.